The second of a series of regularly updated Viewing Rooms highlighting particular series of works from Dennis Creffield’s career.

-

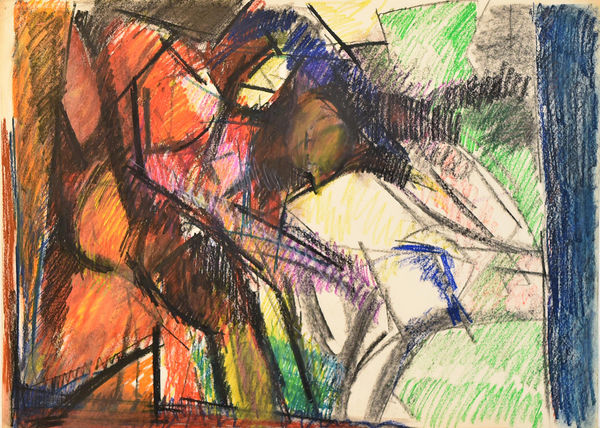

The Lovers, 1970–72

-

‘Naked gropings – through the paint – with whiskers, nose and body all alert’

At the beginning of the 1960s, Creffield’s career was blossoming. He had recently graduated from the Slade, where he won the Tonks Prize for life drawing; the nudes he had completed during these time, radically abbreviated and revelling in the ability of oil paint to appear at once fleshly and sculptural, anticipate his Lovers in their modelling.

In 1961 Creffield received an award in the inaugural John Moores painting prize; his brooding cityscapes, influenced by his former teacher David Bomberg , were included in the Arts Council’s Six Young Painters touring display. He moved to Leeds in 1964, teaching for several years at the university as a Gregory Fellow – but the transformative moment came in 1968, when Creffield moved to Brighton. He later described the profound impact it had on him to Lynda Morris: ‘I was enraptured by the light and movement in the world outside my windows. It was such a change from the inland city airlessness of Leeds and London.’

It was the beginning of Creffield’s experimentation with a brighter, more airy palette, eschewing the earth tones that predominate in the work of Bomberg. His vivid series of semi-abstract seascapes of Brighton pier from this time were the first real indication of Creffield’s abilities as a daringly individual colourist, which would come to fruition two years later in the heat of The Lovers.

-

Reclining Nude, 1959

-

Sea from Studio, 1985

-

‘The way to appreciate them is with the body as well as the eye’

The poet Peter Redgrove, who became a firm friend of Creffield’s while he was in Leeds, said of the artist that ‘I have not met such a cavalier’. Sensuousness was a guiding principle in art as in life, influencing his conception of religion – through the doctrine of incarnation, in particular – as much as it did of painting.

Looking across the charcoals, pastels and oil paintings that comprise The Lovers, is to see how the artist refined the composition across these various mediums to imbue the casual eroticism of the two women embracing – a scene derived from a 19th-century photograph of a bordello – with both architectural monumentality and spiritual grace. The deep mauves, airy yellows and sky blues cause the eye to dance across the canvas; Creffield declared that they were not ‘anecdotal, descriptive or abstracted, but sensory tactile perceptions – naked gropings – through the paint – with whiskers, nose and body all alert’.

When The Lovers were shown at AIR Gallery in 1980, they were displayed alongside paintings from Creffield’s series depicting The Visitation – paeans to the mystery of pregnancy – as well as a group of works representing ‘dreams of fair women’. For Creffield, each was united by having been ‘shaped by a physical sense of the event.’ This show was lauded by the critic Peter Fuller, who later declared that Creffield, along with Auerbach and Kossoff, proved that Britain had artists ‘every bit as good as, say, De Kooning’ – and while comparisons between Creffield’s style and that of the Abstract Expressionist painter have been made, Creffield’s synthesis of the carnal with the spiritual is entirely his own. The Lovers is the moment that he first achieved it, setting the stage for his later religious works, and marking him out as an daringly original figure in the history of post-war British art.

-

The Lovers, 1970–72

The Lovers, 1970–72