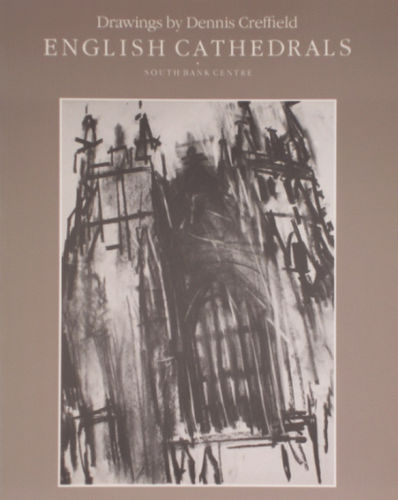

Introduction to English Cathedrals: Drawings by Dennis Creffield, exhibition catalogue, Southbank Centre, 1987

NO ARTIST HAS EVER BEFORE drawn all the English medieval cathedrals – not even Turner. I've dreamed of doing so since I was 17 when as a student of David Bomberg I drew and painted in the cloisters of Westminster Abbey.

This dream finally came true – forty years later – in 1987 when Michael Harrison, having seen some drawings of mine of Wells Cathedral which the Arts Council had bought, asked me if I would be interested in drawing all of the cathedrals for an exhibition to tour the regions. This exhibition is the produce of my joyful acceptance of his inspired offer.

We thought that as an introduction to the exhibition it would be interesting if I wrote something about the experience and the problems which arose out of this unique adventure. And also some thoughts on drawing and on the cathedrals.

The following description of the project was written shortly before setting out on St Valentine's Day 1987:

"The English cathedrals are well known and are visited by thousands of tourists every year. But while generally acknowledged to be works of art, they exist for many people in that part of the aesthetic spectrum called picturesque - together with cream teas and thatched cottages.

In fact they are – together with the plays of Shakespeare – arguably the finest works of native English genius that exist. Not just quaint relics of the past – but audacious and living lessons.

The analogy with Shakespeare's plays is exact – in terms of their quality – and in respect of the staleness which comes with over-familiarity. The problem for the director of a Shakespeare play is how to help the audience experience it freshly. This is what I shall try to do with the cathedrals.

All the many admirable books about the cathedrals have been written by scholars. There is no book in English like Rodin's Cathedrals of France – which is not an architectural treatise but a loving and passionate advocacy of them. Ruskin wrote extensively – and passionately – about Gothic – but within a much broader polemic.

The privilege given me to visit and draw all the cathedrals will be a pilgrimage of learning – a learning that I want to share with others. It is also dauntingly delightful – like being asked to perform the Goldberg Variations.

And variations is the right word. The English cathedrals form a stylistically homogeneous group – quite distinct from continental models. Put very simply – with one exception (Exeter) – they are all cruciform in plan with a tower over the crossing. This deliciously simple motif is never repeated in the same way at any of the 26 cathedrals I hope to visit. It is this idea of variations on a theme that gives formal unity to the project.

From February to November 1987 I drove all over England in a motor caravan. I experienced the changing seasons and the varying length of day as I hadn't done since childhood – I was up before the sun and tucked up in bed before it was dark.

I visited all the cathedrals – most of them twice. Each day I drew them – each night I slept in their shadow – and their shapes filled my dreams.

What problems I had all arose from time pressure – the project had to be completed by late Autumn. Put simply, 26 cathedrals multiplied by 1 week equals 6 months equals a marathon.

Not too tight a schedule for someone who knows how to draw - who could arrive - do their thing and move on. But I wanted to learn to draw at each cathedral – I wanted, if possible, to let the cathedral make the drawing. Also, like many artists, I'm allergic to people watching me draw – I become self-conscious and lose concentration. This situation was made worse because I was working on a large scale and so it was difficult to be unobtrusive – (in retrospect there were comical moments while trying to hide and draw under my large umbrella – shy person undressing on beach).

So, unless I could find a reasonably private position in front of one of my two chosen aspects – the tower crossing or the west front – which was a rare occurrence – I had to work when no one was about. This meant early morning. Fortunately we must be the latest risers in the world. And apart from milkmen, paper boys and the odd jogger, you have the world to yourself between 4 and 7 of a summer's morning.

Unfortunately, this summer advantage is partly negated by a super-abundance of foliage everywhere. The English are dangerously addicted to planting trees around their cathedrals. This well intentioned philistinism – like sticking a large pot-plant in front of a Giotto – has been going on for a long time but now it seems it has got completely out of hand – a royal visit or simply the gardener's whim is sufficient. No long term view is taken of how it will affect the look of the building. The result is that some aspects are partly or wholly obliterated from view for half the year. (Architectural photographs are almost always taken in winter.)

So, although summer has long hours and good weather – (in fact for me it rained nearly every day) – there are too many trees and too many people about to take advantage of it. (It's estimated that more people visit Canterbury Cathedral now in one year than were alive in this country in the 14th century.) The winter is not very good for obvious reasons and Spring passes all too rapidly.

All of this meant that the notional time of one week was in fact whittled down to the actual time of the swiftly moving present which I had to grasp or miss. I had to learn to draw fast and shoot from the hip.

This ever urgent pressure was also the cause of the most fatiguing part of the journey. Not physical fatigue but emotional – the relentless progress (stagger) from one confrontation to the next without pause. Durham followed by York followed by Lincoln followed by Norwich and so on – it was like wrestling with an endless succession of giants (or angels). And needing to come back each time with a hair from their head.

“It is not possible to get the complete expression of the apse of a Gothic cathedral, into a picture, as the elevation cannot be drawn as a vertical plane in front of the eye, the head needing to be thrown back, in order to measure their height, or stooped, to penetrate their depth.” – Ruskin Modern Painters IV

This is a clear description of the inability of the academic approach to with the complexity of human perception. (The late-Renaissance academy had – for the purpose of drawing and painting – reduced visual perception to a static-one-eyed viewpoint- geometric perspective.)

The medieval artist's idea of the perceptual was as of a faculty of imaginative understanding. And so in his art space, time and distance are not governed by measurement but by the relative significance of the constituent parts.

I belong to the progeny of Cézanne – that self-described – "primitive of a new art". He inaugurated an era in which the very complexity and uniqueness of perception is itself the subject of the painting.

I am not interested in creating an illusion of reality – nor in making a symbol of it. But in trying to find a substantial form for its substantiality – an image of actual experience – the wound unbound.

Yes, Ruskin – it is possible. To look up and to look down – and to unite these separate moments of time and physical movement – by means of the continuous imagination of memory.

I do not look at the cathedral as if through a letterbox – neither do I draw it so.

To describe my work I would like to reclaim the word "impressionist". It's a waste that it should only be used to describe the work of certain 19th century painters – who didn't choose it themselves anyway.

I use it in the way we do when we say – "that is impressive" or "I am impressed".

Here an "impression" is not a fleeting optical moment but a total response. A perception in which eye, mind, body and imagination are all one at the same time together.

Understood in this way I am an "impressionist".

"Remember the impression one gets from good architecture, that it expresses a thought. It makes one want to respond with a gesture.

"Architecture is a gesture.”

These two thoughts of Wittgenstein's state with clarity and distinction my approach to drawing the cathedrals.

By gesture (I mean) the significant stance that characterises and identifies people and things. Van Gogh remarks that we can identify an acquaintance from a great distance because we recognise their stance. We recognise familiar trees and animals in the same way. (This is not simply shape – the gesture is an animate principle.)

Each cathedral is a gesture – I respond with my gesture and the drawing is a mutual embrace. (And the marriage of two minds.)

I find drawing extremely difficult. I don't do it because I enjoy it. But because it's the only way that I can understand things.

This writing has been an agony – words slide about and don't have any density- no reality in themselves – only in what they mean. Only drawing is real – and I only feel real when I draw.

"Architecture immortalises and glorifies something. Hence there can be no architecture where there is nothing to glorify.

These drawings are my glory to their glory which came from the glory of God.

(Unless otherwise ascribed all the quotations above are from Wittgenstein Culture and Value or Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.)