Review, ‘Dennis Creffield: A Retrospective’, published in The Times, 2005

MIGHT AS WELL GET it out of the way immediately. Yes, Dennis Creffield is a Bomberg survivor. That is to say, between the ages of 16 and 19 he was a pupil, and indeed an enthusiastic disciple, of the great English expressionist David Bomberg. But now he is 74, and sick and tired of the Bomberg connection being constantly dragged up.

It is not as though it has ever been of much advantage to him. When he was one of the Bomberg entourage, showing with Bomberg’s support organisation of students the Borough Group, it was rather you and me against the world, babe: Bomberg himself was in the wilderness, virtually forgotten — and when not forgotten reviled — by the outside world. After his death in 1957 things changed rapidly. When Creffield entered the Slade in 1957 any hint of Bomberg was definitely anathema to the school’s leaders; by the time he left in 1961, William Coldstream was Slade Professor, and Bomberg was increasingly approved. The fact of having been his pupil provoked high expectations and damning comparisons, even if the critic had thought nothing of Bomberg while he was alive.

Now, nearly half a century on, the Bomberg connection is neither here nor there. Anybody looking at Creffield’s first retrospective, at Flowers East, will encounter a mature, brilliantly individual artist. Though he is probably best known as a draughtsman, he proves to be equally adept at painting in oils, and the paintings are not even obviously “draughtsman’s painting”, implying that the skeleton was there first and was then virtually coloured by numbers.

The most surprising thing about the show, given the outstanding quality of the paintings, is that they and the drawings are given absolute parity of esteem. There is no sense here that the drawings are “just drawings”. Creffield himself, a small spry man who looks about 20 years short of his chronological age, is delighted with this. “The thing is, I have never made any distinction between paintings and drawings myself. They are both exercises of the same artistic function, and what is crudely called black-and-white is really as nuanced and various as any range of colours.

“For most of art history the drawing has been regarded simply as a painter’s aid: he would sketch out a composition or record a detail that way, and when the painting was finished the first drawings would be abandoned, unless some eager-beaver follower or researcher dug them out of the waste. It is only a comparatively recent thing for drawings to move out of the field of illustration and become recognised as valid artworks in themselves. And that recognition is still far from complete.”

I remember that when I was on the selecting panel for the second Discerning Eye exhibition, the thing that most worried another selector, the distinguished collector Sir Brinsley Ford, was the dearth of drawings submitted, which he blamed on the demise of the life class in nearly all art schools. Is it a problem that students are no longer taught to draw, as though the discipline is quite irrelevant to art in the 21st century? After all, when, last year, the Royal Academy instituted a special gallery in the Summer Exhibition for drawings, many unexpected artists, such as Damien Hirst, seemed to jump at the chance.

“I find it very difficult to generalise,” Creffield says. “My own experience is this: Bomberg made no distinction between drawing and painting, both being based primarily on an appreciation of, and ability to render, the weight and mass of the subject. Some of his finest works, such as the thrilling landscapes of Ronda, are large charcoal drawings based on this principle.

“When I went on to the Slade I found their approach to drawing unsympathetic, tending towards a very close, finicking particularity rather than making a satisfactory work of art. But since the Slade then was an entirely postgraduate institution, with no classes or formal teaching, I went right on drawing the way Bomberg had encouraged.

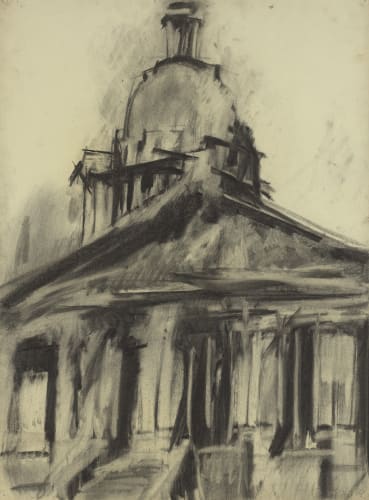

“If people associate me particularly with drawing it is because, quite by chance, my first big public success was with the series of large-scale drawings of all 24 medieval English cathedrals commissioned in the Eighties by Michael Harrison for a South Bank touring exhibition. That was something I had dreamed of doing ever since I had first worked in and around Westminster Abbey in 1948 (one of the 1948 paintings is in the present show), and I lived in a camper van for a year, moving from one cathedral to another, working from dawn to dusk and particularly delighting in the times, early and late, when I had them all to myself.

“And I found that, living in such intimacy with them, I fell in love with each one for its own qualities. I think you have to fall in love with a subject before you can draw or paint it.”

Certainly the retrospective is filled with evidence of love poured out, whether it is for the subject of his own fatherhood in the wonderfully tender, unsentimental drawings of Anxious Father, Anxious Baby, or in the paintings and drawings inspired by A Midsummer Night’s Dream (which originated in a commission to paint something suitable for a bridal bedroom and spiralled out from there), or by Mozart’s portraits or Petworth seen — but how differently — from the same angle that Turner painted it, or by the Louis MacNeice poem about snow and roses.

Love may not always be enough for the artist to work from, but on the evidence of Creffield’s life-work, it is the best possible place to start.